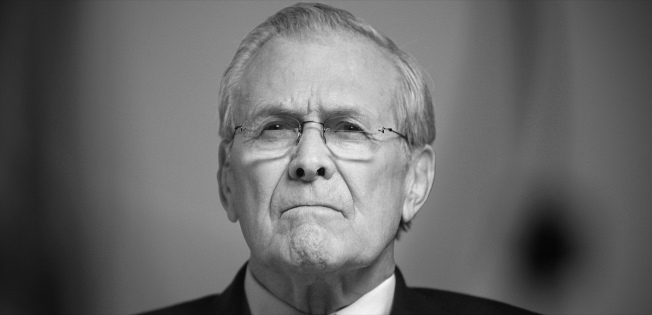

In THE UNKNOWN KNOWN, Academy Award-winning director Errol Morris (THE FOG OF WAR) offers a mesmerizing portrait of Donald Rumsfeld, the larger-than-life figure who served as George W. Bush’s secretary of defense and as the principal architect of the Iraq War.

Rather than conducting a conventional interview, Morris has Rumsfeld perform and explain his “snowflakes” — the enormous archive of memos he wrote across almost fifty years in Congress, the White House, in business, and twice at the Pentagon. The memos provide a window into history — not as it actually happened, but as Rumsfeld wants us to see it.

By focusing on the “snowflakes,” with their conundrums and their contradictions, Morris takes us where few have ever been — beyond the web of words into the unfamiliar terrain of Rumsfeld’s mind. THE UNKNOWN KNOWN presents history from the inside out. It shows how the ideas, the fears, and the certainties of one man, written out on paper, transformed America, changed the course of history — and led to war.

THE UNKNOWN KNOWN – An Interview with Errol Morris

THE UNKNOWN KNOWN begins with an image of a seemingly infinite body of water. Why?

In my film, VERNON, FLORIDA, there’s a man named Albert Bitterling who tells a story about two sailors who are looking out over the ocean, and one sailor says to the other: “You know, there’s a whole lot of water out there.” And the other sailor says, “Yeah, and that’s just the top of it.”

The water is an expression of the unknown. You are looking out at this shimmering surface of the water, and wondering: What is underneath all that? That is the mystery I have investigated so many times in my films — what is going on in people’s heads? And what I usually find is self-deception, self-importance and self-satisfaction — phantasmagorical thinking. I spent 33 hours with Donald Rumsfeld. And what I discovered was that he was the quintessential Errol Morris character.

Why did you want to interview Rumsfeld? Some might say he’s already had more than enough opportunities to tell his story.

Many people are so angry at Rumsfeld that they haven’t even bothered to look at him. Maybe it’s too painful. Better just to reject him out of hand rather than to actually think about him.

What got me started is that I read his autobiography, Known and Unknown — a brick of a book — in 2011, and discovered for the first time that he had written tens of thousands of memos — 20,000 during the Bush administration alone.

I find these memos oddly fascinating. I don’t know exactly what they are. Are they merely instructions to his colleagues and associates? Are they genuine attempts to understand various policies, decisions or ideologies? Or were they written because Rumsfeld wanted to determine how he might be seen in the future — to create his own first draft of history? Or all of the above?

The memos give us a way of looking inside of his head. I saw this as a chance to do history from the inside out, using the memos as a way of exploring the disjunction between how Rumsfeld wants to be seen, how he wants people to think of him, and who he really is and what he’s really done. The opportunity for him to read these memos, contextualize them, discuss them with me, was, to me, the most powerful reason for making the film.

To say that I came into this movie without strong ideas about Rumsfeld and his policies would be fraudulent and disingenuous, at best. I was very much against the Iraq war, and I still am—I think it was a terrible mistake. But I believe I made this film in the spirit of inquiry, with a genuine desire to investigate, a desire to find out something that I might not have known before.

THE UNKNOWN KNOWN is taken from a famous statement Rumsfeld made during a 2002 press conference before the invasion of Iraq. Why did you choose this as your title?

Rumsfeld is a person everybody knows, whose image was ubiquitous during the first few years of that administration. And yet, who is he? Who is this person, who we all know on some level? I see Rumsfeld as an unknown known.

Few people realize that the words “Known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns, were in a memo titled “To Discuss with P.” dated May 21, 2001 — months before September 11th. Also included in that memo is the phrase “the absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence.” When Rumsfeld famously trotted out the “knowns” and the “unknowns” on February 12, 2002, it was in response to a question from Jim Miklaszewski of NBC News about the link between Saddam Hussein and terrorist groups. Instead of answering Miklaszewski’s question, he deflected it into a kind of philosophical evasion: You see, there are the things that we know about, the things we don’t know about, and the things we don’t realize we don’t know about. And then another reporter interrupts and says, “But he didn’t ask you something that was unknowable. He asked you if you knew of evidence that Iraq was supplying, or willing to supply, weapons of mass destruction to terrorists.” In other words, we don’t want to hear a discussion of the nature of evidence — we’re going to war!

To me, one of the most remarkable things in the movie is that as the Iraq war is clearly going south — rather than ever admit it, Rumsfeld talks more and more about the meaning of words, about semantics, about this dictionary versus that dictionary, this definition versus that definition. I like to think that George Orwell would have looked kindly on this effort.

A lot of Rumsfeld’s maxims are contradictory. He states one thing and then its opposite. He says: “If you wish for peace, prepare for war.” He also says: “Belief in the inevitability of conflict can become one of its main causes.”

A mathematician friend of mine saw a cut of the film at MIT, and said, “Are you aware that he constantly is uttering contradictions?” And I said, “Yes, the thought has occurred to me.” Then she also pointed out to me something that I also was aware of, that is absolutely true — in logic, from a contradiction, you can prove anything.

A lot of Rumsfeld’s beliefs — like the need for an aggressive defense to have peace — seem to have their roots in his ideas about Pearl Harbor as a “failure of imagination.”

I was very scared by that line. Are you supposed to just imagine anything? And act on it?

He takes these words from an introduction written by Thomas Schelling for Roberta Wohlstetter’s book Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, about the intelligence failures that led to Pearl Harbor. But those words aren’t in Schelling’s introduction.

And what do you get? The war in Iraq. You don’t need oil, desire for world hegemony, Islamofascism, as reasons to go to war. All you need is a kind of crazy thinking. You imagine the worst and treat it as if it’s really going to happen. He says: “I wish we could see around corners.” Well, to see around corners, you have to look.

Sometimes when Rumsfeld tells stories about other people, it seems like he’s talking about himself.

And he doesn’t seem to be aware of it. It’s because we all have an infinite capacity for denial. We always try to avoid looking at ourselves. Isn’t it what makes life possible?

Do you think you were hard enough on him? Would he have told you more if you pushed him more?

Did I at any point ever say to him: “I think what you did was deeply wrong, and against international law”? No, I did not. And I can defend the decision not to do that on a number of levels. If the goal is to terminate the interview quickly or to create the frisson of a clash where the interview subject gets up and walks out of the room in a huff — that would be easy to achieve at any point. That was not my intent. I wanted to learn something from the interviews — not just provide the expected, dramatic confrontation.

I came to realize that he was answering my questions, in his own way. He was telling me a very powerful story about himself and how he sees the world, and that it was all there.

Now, there is a naïve notion about investigative journalism: that we’re going to be given the key to a lock box and we’re going to be allowed to listen to the deepest, the darkest secrets of history. And often the most frightening thing is that we open the lock box and it is empty.

What’s the connection between THE UNKNOWN KNOWN and your previous film THE FOG OF WAR? Between Robert McNamara and the Vietnam War and Donald Rumsfeld and Iraq?

THE FOG OF WAR raises the question: “Is McNamara really sorry? And does being sorry make a whit of difference when we’re talking about the deaths of millions of people?” There is no such doubt about Rumsfeld. He’s unapologetic. He would like us to think that the Bush administration did the best they could in a stressful moment in our history. But more than that, he doesn’t want to show weakness, or to second-guess himself. The movie I have made with Rumsfeld is vastly different from THE FOG OF WAR. It is a character study of a very different kind of character: it is about a mind that appears to be open but may in fact be locked up like a safe.

For me, THE UNKNOWN KNOWN is a deeper movie. It asks: “Do we, as people or as a country, really know who we are and what we’re doing? Or are we all trapped inside a set of ideas, inside an image of ourselves, that prevents us from seeing the truth until it’s too late?”

My wife, Julia, likens Robert McNamara to the Flying Dutchman, traveling the world looking for redemption that he’ll never find. And she sees Rumsfeld as the Cheshire Cat — all that’s left at the end is the smile.